Introduction to the Project:

The story of the Cristero War and the Mexican Revolution is often told through the lens of military conflicts and political upheavals, but an equally important chapter lies in the humanitarian efforts that followed. This project aims to uncover the role of San Antonio as a crucial sanctuary for Catholic exiles fleeing religious persecution in Mexico during the early 20th century. By examining the involvement of the Diocese of San Antonio, the Catholic Extension Society, and U.S. government officials, this research sheds light on the extensive efforts made to support displaced clergy and laity. Through these findings, we gain a deeper understanding of how transnational networks of faith and diplomacy shaped the experience of exile and refuge during this tumultuous period.

Finding Aid created in partnership with the Archdiocese of San Antonio

Historical Background of the Mexican Revolution and Cristero War

The Mexican Revolution (1910–1920) was a period of civil and political strife that dramatically reshaped Mexico’s government and society. It began as opposition mounted against the long-standing dictatorship of President Porfirio Díaz, who had ruled Mexico for over three decades, favoring industrialization and foreign investment while suppressing dissent. Francisco I. Madero, a wealthy reformist, emerged as the leader of the opposition, advocating for democratic elections and an end to Díaz’s authoritarian rule. His movement gained widespread support, leading to Díaz’s resignation and exile in 1911.

Madero was elected president but struggled to implement immediate reforms, leading to dissatisfaction among revolutionary factions. In the southern state of Morelos, Emiliano Zapata launched an armed revolt demanding land redistribution, while conservative forces and remnants of the old regime opposed Madero’s leadership. In 1913, a coup known as the Decena Trágica (Ten Tragic Days) led to Madero’s assassination, orchestrated by General Victoriano Huerta, who then seized power.

Huerta’s dictatorship faced fierce resistance from multiple revolutionary leaders, including Venustiano Carranza, Álvaro Obregón, Pancho Villa, and Zapata. These factions united to overthrow Huerta in 1914 but soon turned against each other. Carranza, aligned with middle-class reformists, sought to consolidate power and draft a new constitution, while Villa and Zapata continued to fight for radical social reforms. The internal struggle resulted in prolonged violence and shifting alliances.

By 1917, Carranza enacted the Mexican Constitution, introducing significant labor and land reforms. However, political instability persisted, and Carranza was assassinated in 1920 during a revolt led by former allies. The following decade saw continued power struggles and the rise of government-enforced anticlerical policies, culminating in the Cristero War (1926–1929), a bloody conflict between the Mexican government and Catholic rebels resisting religious persecution.

Refugees in the Early Period (1910–1920)

As conflict intensified in Mexico, many Catholics, including clergy and laypeople, sought refuge in the United States. The Diocese of San Antonio, under the leadership of Bishop John W. Shaw, played a pivotal role in accommodating these exiles. With support from the Catholic Extension Society, Bishop Shaw provided shelter for displaced Mexican clergy, while nuns and other religious figures found refuge among their American counterparts. To finance these efforts, he established the Mexican Refugees Relief Fund, which collected donations from Catholic organizations, the Diocese, and the Catholic Extension Society.

The Diocese welcomed several prominent Catholic leaders, including Archbishop José Mora of Mexico City, Archbishop Leopoldo Ruiz of Michoacán, and Archbishop Francisco Plancarte y Navarrete of Linares. To support displaced seminarians, the Sisters of Divine Providence helped establish St. Philip of Neri Seminary in Castroville, which operated under the direction of Bishop Juan Herrera of Tulancingo.

Beyond religious efforts, U.S. government officials also played a role in assisting Mexican refugees. Congressman James L. Slayden of San Antonio coordinated with the 63rd U.S. Congress and the State Department to facilitate the relocation of clergy and laity. Additionally, some priests and nuns were relocated to Cuba from Veracruz with help from Bishop Shaw.

Refugees in the Late Period (1920–1930)

As conditions temporarily improved, some clergy and laypeople returned to Mexico. However, the enforcement of the anticlerical policies outlined in the Mexican Constitution of 1917 reignited religious persecution, leading to the Cristero War (1926–1929). Unlike the previous period, this time, many lay Catholics took up arms in resistance.

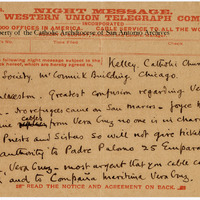

During this renewed persecution, the Archdiocese of San Antonio, now under Archbishop Arthur J. Drossaerts, once again provided refuge for fleeing clergy and lay Catholics. Among those exiled were Archbishop José Mora of Mexico City and Bishop Ignacio Valdespino of Aguascalientes, who became key figures in Catholic social action movements. Unlike the earlier period, this era saw an increase in violence against Catholic exiles, with reports of assassinations and kidnappings. The situation escalated to the point where even the Apostolic Delegate in Mexico was forcibly expelled, underscoring the severity of the conflict.

Archbishop Drossaerts, in coordination with the Catholic Extension Society, arranged housing and assistance for refugees. He maintained close contact with Catholic leaders across the United States, successfully mobilizing nationwide support for those fleeing religious persecution. Through these efforts, the Archdiocese of San Antonio solidified its role as a sanctuary for Mexican Catholics caught in the upheaval of revolution and war